Summer beach season doesn’t officially start until Memorial Day, but there is already a major increase in the number of beachgoers traveling through the canyons and along Pacific Coast Highway in pursuit of sand and sea.

The ocean is just a few yards away from the highway in many places on the route from Santa Monica to Topanga or from Topanga to Malibu, but many travelers have never taken the time to stop and look around, not even when they are stuck in traffic.

Today, one of the most conspicuous features of the coast east of Topanga are the old concrete and rock groins, constructed in the early 20th century in an unsuccessful attempt to make the beaches wider. These structures are sometimes referred to as jetties—similar devices, but used on either side of an inlet, or breakwaters, a longer structure that is often used to create artificial harbors or anchorages.

Groins effectively catching sand, building up the beach on the up-current side of the barrier. However, they also interfere with a process called longshore sand transport, causing sand erosion on the down-current side of the groin. This creates a sort of scallop pattern along the shore, ultimately eroding the entire beach.

There are several examples of boulder groins along Will Rogers State Beach, and another at Gladstone’s Restaurant that is almost long enough to qualify as a small breakwater. The nearest true breakwater is off the 100-year-old Santa Monica Pier. It was installed decades ago to protect the structure from storms and waves.

A pair of dilapidated concrete and metal groins are visible on the stretch of coast between Sunset Mesa and Sunset Blvd., remains of a beach widening and flood control project from the 1950s. One of the strangest remnants of that era is located at Tuna Beach, where a concrete and metal groin connects to a large boulder. It’s a good example of the impact groins have on beach erosion: the sand on the up-current side at this site is frequently as much as 15 feet higher than the eroded section immediately down-coast.

Tuna Beach is a good place to observe how boulders have been used to buffer PCH and, but it’s just one of many stretches of PCH with an “armored” or “hardened” coast. One of the longest contiguous sections runs from just east of Topanga Canyon Blvd. to just west of Coastline Drive. Also known as “riprap” revetment, this kind of coastal armoring is intended to protect property—or in this case, the highway—from erosion, but it’s controversial. Research confirms that riprap contributes to sand and habitat loss, and that all forms of coastal armoring speed erosion in down-coast areas that are not yet hardened.

An even more drastic form of coastal armoring called a sea wall can be spotted opposite the Getty Museum at Sunset Mesa, where a parking lot and beach access staircase are located on the site of a long vanished restaurant called The Jetty, which burned down in 1981.

The 640-foot-long vertical seawall is almost invisible from street level, but drive by on a day when the tide is high and the surf is big and the stray from waves hitting the concrete wall shoot over the 15-foot sea wall with a sound like thunder.

Long before The Jetty Restaurant, the stretch of coast was once home to a natural landmark, Castle Rock. The towering 50-foot-high column of natural stone was dynamited to widen PCH in 1945 but a second, smaller stone, the Haystack, is still visible.

Castle Rock outlasted its equally famous neighbor, Arch Rock, by nearly 50 years. The arch stood at the site that is now home to Maestro’s Club. It was the gateway to adventure for motorists in the days when the coast route was an unpaved single-track, and its hazards included flooding at high tide and obstacles like cattle or sea lions.

Arch Rock appears in numerous picture postcards from the turn of the previous century. Nathan Masters, the host of the KCET documentary series Lost L.A. has called Rock Arch “the defining image of the Southern California coast” for many 19th century tourists, but its celebrity wasn’t enough to save it.”

The arch is said to have been illicitly dynamited in the night in 1906 by individuals working for the railroad company that sought to build a route across the privately owned and off-limit Malibu Rancho.

Arch and Castle Rocks aren’t the only iconic coastal landmarks to have completely disappeared. In fact, In fact, the things that are no longer here are a major part of what makes this stretch of coast unique.

Houses once lined more than a mile of the coast from Topanga Creek to Will Rogers Beach. Built in the 1930s and ‘40s on land owned by the L.A. Athletic Club, they were demolished in the 1970s.

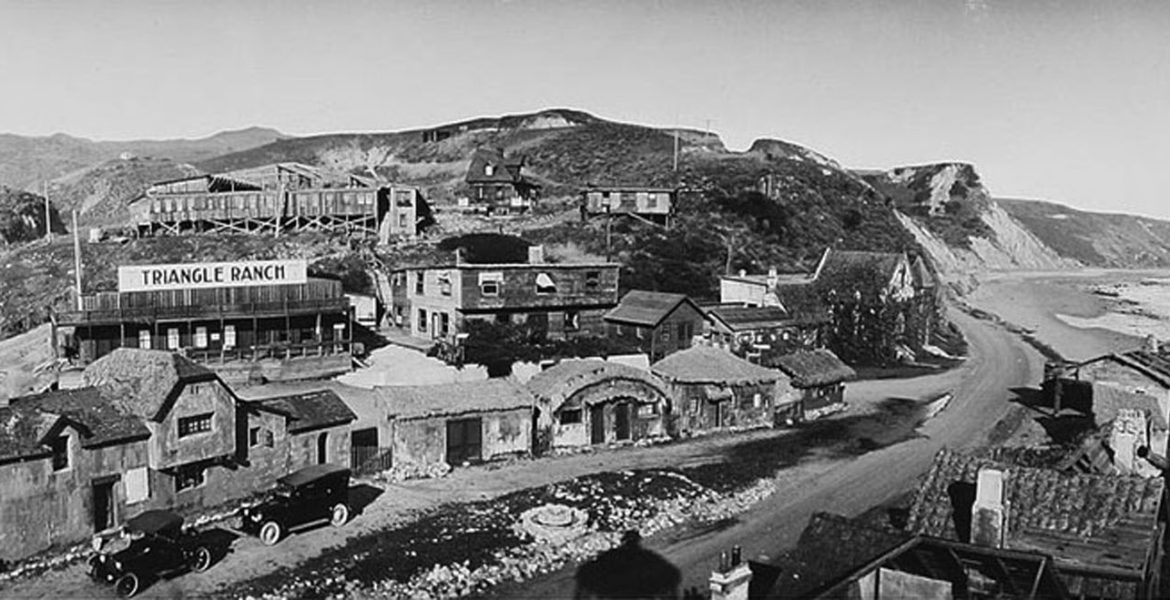

In the early days of silent film, the town of Inceville once straddled Sunset Canyon at the coast. The film set built by pioneer filmmaker Thomas Ince included an entire Scottish village, a medieval church and a New England lighthouse. Only the church survived a catastrophic 1922 fire. A few decades later, that final landmark of L.A. film history also disappeared.

Nothing remains of the mile-long pier built at the mouth of Temescal Canyon in 1892 in a bid to make the Santa Monica Bay into the Port of L.A. The pier, complete with railroad tracks constructed by Southern Pacific and a tram line from Santa Monica, served cargo and passenger ships until 1913, when it was damaged in the same storm that destroyed the old Redondo Beach Pier. What was left of Long Wharf was demolished in 1933. Comedian Will Rogers acquired the beach as part of a 186-acre ranch in the 1920s. Rogers died in a plane crash in 1935. The property became state park property after the death of his widow in 1944.

A restaurant and bathhouse with an ornamental lighthouse tower was built on the site in the 1920s. It also became a landmark. For a number of years after the restaurant closed it served as lifeguard HQ. The miniature lighthouse at the entrance to Will Rogers State Beach pays homage to the structure that was demolished in 1972.

Visitors to Will Rogers State Beach, seeing the sign for California “Historical Landmark Number 881 site of the Port Los Angeles Long Wharf,” occasionally mistake the formidable Will Rogers storm drain for the foundations of the wharf. All of the major creeks in this stretch of PCH travel under the highway through a box culvert and out to sea via a pier-like concrete structure, another legacy of that 1950s flood control project.

The creeks may be channelized and and the shore armored with riprap, but this stretch of PCH remains unusual because the decisions made here have frequently resulted in removing development rather than increasing it. Instead of the industrial Port of Los Angeles envisioned in the 1890s, there is Will Rogers State Beach. Instead of the wall-to-wall houses found west of Topanga at Big Rock and Carbon Beach or east at Santa Monica, there is Topanga State Beach. It’s something to think about while stuck in the inevitable weekend PCH beach traffic, or one could just enjoy the view.