Continuing our series on the U.S. Constitution Jimmy Morgan, MMN columnist of History in the News, explores Article 1 of the Constitution. He notes how the choice to establish three branches of a central government does and doesn’t work for a democratic republic in the 21st century.

“If men were angels, no government would be necessary.”

—Federalist No. 51

With this less-than-flattering opinion of mankind, delegates at the Constitutional Convention of 1787 gathered in Philadelphia to address the shortcoming.

Among the delegates was widespread agreement that the powers of a new government should be spread about – in three branches – so that no one person or small group of people would be able to abuse power. This “separation of powers” idea was put forth by Enlightenment philosopher Baron de Montesquieu. Ideally, each branch should “check” (keep an eye on) the others in order to preserve the “separation” and therefore encourage a “balance” of power among the three.

While there has been much talk recently that the branches are “co-equal,” the reality is that the thousands of personalities who have occupied these positions have brought to the equation the force of their personal and political passions. If there have been any angels among them, I surmise their number can be counted on fingers. The result has been an ever-shifting locus of power tempered by the system the 1787 convention created.

Our nation’s history is filled with moments defined by the concentration of power the Constitution was designed to disperse, often during a crisis. Abraham Lincoln suspended basic civil rights during the Civil War; but he got us through it. President Franklin Roosevelt was elected to four terms, had broad influence within the legislative branch, and eventually placed eight justices on the Supreme Court; but he held the country together during the Great Depression and World War II. Very few bemoan the power exercised by Lincoln and FDR but, knowing that lesser men would follow, the Constitution was amended to bolster adherence to its principles.

Despite the presence of Constitutional safeguards to discourage this concentration of power, it is clear that some within our government play outsize roles. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has influenced the impeachment trial of Donald Trump. He also held up a legitimate Supreme Court nominee in order to fashion that judicial body in his vision. And, while you may not be troubled by McConnell’s moves, we should all take notice that one man—beholden primarily to a majority of the voters in Kentucky every six years, has a great deal of power.

Most recently, the president has begun to flex his executive muscle in order to deal with a public health crisis. During moments such as these, we need clear, singular leadership and sometimes the urgency of the matter leaves little time to consult with 535 lawmakers. However, while a crisis may demand immediate and difficult steps, we should all be cognizant that a crisis also provides an opportunity for those in power to abuse that power.

If this concerns you, the first order of business is to ensure that we all know how it works. It has been my experience that not all of us do.

ESTABLISHING A CENTRAL GOVERNMENT

The first three articles of the US Constitution establish the three branches of government: Legislative (I), Executive (II), and Judicial (III).

Article I establishes the legislative branch wherein the states are represented in a House of Representatives (by population) and a Senate (equally, wherein all states, no matter how large, have the same number of senators (2) representing them). Members of the House serve two-year terms and must be 25 years old; Senators serve six-year terms and must be 30 years old. This branch is responsible for making law; the Executive branch enforces the law; and the Judicial branch interprets it.

The younger age requirement and two-year term of the House were intended to create an environment of lively debate where members must be acutely attuned to their constituency.

Because 2020 is a census year, it’s helpful to understand that drawing congressional maps has been a hot topic for the entire history of our nation.

In 1812, Governor Elbridge Gerry approved a district map for the state legislature of Massachusetts. One of these districts was so unwieldy as to resemble a salamander. Henceforth, districts drawn in a politically motivated manner are referred to with the portmanteau of “gerrymandering.” As the ability to predict the political/voting behavior of Americans has increased with technology, it is now possible to draw districts that heavily favor the interests of those charged with the task. Since this responsibility has typically been the province of state legislatures—and we can safely assume that there are few angels among them—statewide elections in 2020 take on added significance.

Unlike the House, the U.S. Senate is intended to be less subject to day-to-day political pressures in large part due to a six-year term. This allows Senators to be more deliberative and potentially less reactionary to the zeal of the moment.

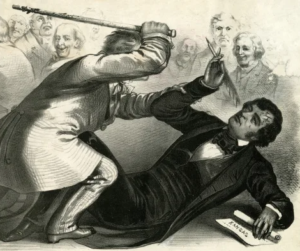

In a manual written by then-Vice President Thomas Jefferson and adopted by the Senate in 1801, members agreed to avoid “hissing, coughing, spitting, speaking or whispering to another” during their deliberations. Indeed, when Senate behavior gets out of control, history tells us that bad things follow. In 1856, abolitionist Senator Charles Sumner was nearly bludgeoned to death as he sat at his desk in the Senate chamber, by a pro-slavery House representative from South Carolina. Less than five years later, the nation was embroiled in civil war.

The Senate was recently the sight of another spectacle, one arising from the fact that Article I prescribes that the House and Senate make their own rules of procedure. Typically, a bill (proposed law) passed by a majority of the House and Senate, then signed by the president, creates new law. However, the rules in each body have been crafted to manipulate what would otherwise be an inherently democratic system.

Article I also calls for a census in 2020 as it has every ten years since 1790. This counting of the people determines the relative representation of the states in the House, the number of electoral votes assigned to each state, the demographic information necessary to redraw congressional maps, and the distribution of federal funding to local governments. It is no coincidence that the current administration is heavily involved in this process including the effort to solicit information that might discourage the participation of immigrants and people of color.

As to the primary function of drafting legislation, Section 8 of Article I enumerates powers of the legislature including the power to regulate commerce, coin money, declare war, and “make Laws which shall be necessary and proper.” Of course, “necessary and proper” is subject to interpretation making it the source of many contentious debates.

Like much of the Constitution, however, this “elastic clause” allows the government to deal with issues the Framers could never have anticipated. Given that news and information in the 1780s traveled about the speed of a horse, and that the country’s western boundary was the Mississippi River, we can be grateful that the Framers established a form of government with a little wiggle room.

To wit, Article I acknowledges that the citizens of the United States in the 18th century personally identified more with their state than with the nation as a whole. Yet, things have changed.

By the mid-1900s, World War II had prompted the migration of millions of people* and the war seemed to unify the country. Today, we are a more mobile society and many no longer so strongly identify with a given state. Perhaps it is time to take this new reality into account. There were some good reasons that the Framers emphasized state representation over citizen representation, but a quick review reveals that their arguments simply do not apply as they once did.

Of course, history tells us that making dramatic changes to this sacred document, as suggested here, or otherwise, often requires a crisis.

Given recent events, it appears that the resiliency of our Constitution will be tested once again. Let us just hope we can find an angel or two, at least, to guide us through it.

* The “migration of millions” I refer to are those within the country moving to other parts of the country to work in war-related jobs. This includes millions of African-Americans who fled the rural South to places like Detroit and the West coast (the Second Great Migration). This is meant to back up the idea that people no longer identify with a particular state as they once did. Also, the war actually limited immigration from foreign lands.