In the area where the federal government once operated 10 experimental nuclear reactors, 18 buildings are slated for demolition and mitigation.

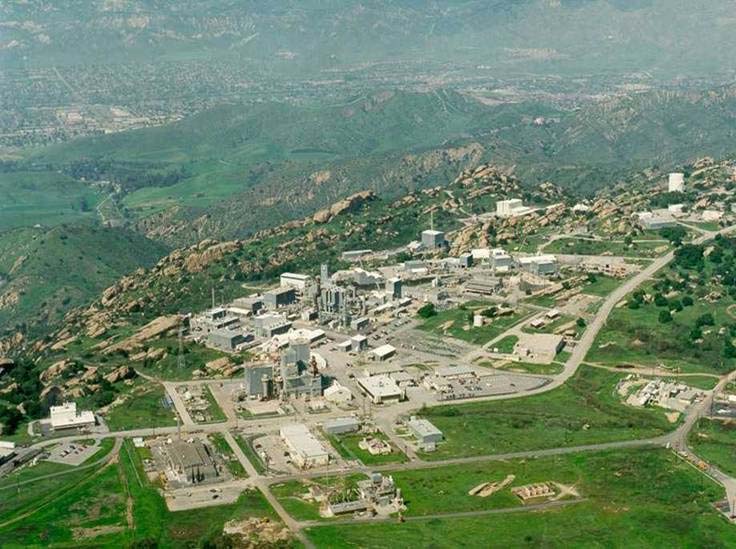

The Santa Susana Field Laboratory (SSFL) sprawls across nearly 3000 acres in the Simi Hills at the far north end of Topanga Canyon Blvd. Rocketdyne, the original owner of the property, developed the field lab for research, development and testing, but it also leased portions of the test facility to the federal government.

From 1948 to 2006 thousands of NASA rockets were tested at the site, but the field lab was also home to as many as 10 small nuclear reactors, operated by the Atomic Energy Commission, the predecessor to the Department of Energy (DOE).

The nuclear reactors were located at the Energy Technology Engineering Center (ETEC) in Area IV, the site of a notorious experimental liquid sodium nuclear reactor accident in 1959, that released massive amounts of radioactive contamination into the environment in what is now regarded as the worst nuclear accident in US history. That was just one of a number of nuclear incidents at the field lab.

Area IV has already undergone extensive mitigation. Photos from the 1980s, when the nuclear program was already coming to an end, show a small city, with nearly 300 buildings. Today, only 28 structures remain, but the chemical and radioactive contamination continues to be a concern. When the Woolsey Fire ignited in Area IV last November 8, new concerns were raised over whether the fire released contamination from the soil or from burning plant material.

Now, the US Department of Energy has issued a Record of Decision (ROD) to enable the demolition of most of the remaining structures at the ETEC site. The action came just weeks after Energy Secretary Rick Perry visited the site. Perry, the first Secretary of Energy to visit the site of the worst nuclear disaster on US soil, released a statement: “As Secretary of Energy, one of my main priorities has been to tackle our enterprise-wide cleanup challenges, including the ETEC site,” he said.

During peak use in the late 1950s and early ’60s, there were ten nuclear research reactors, a “hot” laboratory where plutonium was processed into fuel cores, a nuclear materials development facility, the Radioactive Materials Handling Facility, an assortment of nuclear storage areas, and a waste disposal burn pit.

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) documents reveal the pit was used from 1966 to the late 1970s “for the disposal of metallic sodium and sodium-potassium mixtures, solvents, and radioactively contaminated equipment.”

The EPA also provides details on the July 13-26, 1959, partial reactor core meltdown, which resulted in “localized melting of 30 percent of the fuel elements in the reactor core,” that released radioactive gases into the atmosphere.

A MAJOR SNAG

The EPA lists four other nuclear reactor accidents on site—two additional incidents in 1959, one in 1964, and one in 1969. There were also a number of fires in the hot laboratory, including an out-of-control blaze in 1957 that “spread contamination,” including radioactive dust.

All nuclear research in Area IV ended in 1988. The reactor that malfunctioned in 1959 had already been removed when the decontamination and decommissioning of the sodium test facilities started in 1996, in preparation for the DOE to transfer Area IV to Boeing, the current owner of the field lab, but there was a major snag. In 1989, high levels of widespread chemical and radioactive contamination were uncovered at Area IV, and the site’s troubled history was revealed.

Much of the nuclear research, including the 1959 meltdown, predated environmental regulations. A report by Rockwell International, which owned the site when the faulty reactor was removed in the 1980s, reported that 136,411 cubic feet of radioactive material was removed from the site and reburied in a secure location in the 1980s, but the report suggests that no one was aware of the extent of the contamination. It optimistically indicates that all radioactive material was being mitigated. Instead, the reactor was only part of a much bigger problem that included extensive chemical groundwater contamination and widespread radiation.

Even today, there are few details about the controversial disposal techniques that included burning chemicals and radioactive waste in open pits. There are allegations that thousands of gallons of radioactive sodium coolant may never have been fully accounted for.

The DOE press release states that the agency “will now work with its contractor to finalize demolition plans and processes.” The process is anticipated to take two years, if it doesn’t encounter additional snags.

“I recently had the opportunity to travel to California and visit the site where I was able to see first-hand the progress that has been made, and learn about the remaining challenges,” Perry announced. “The issuance of this ROD marks a significant step toward the final cleanup of this site.”

The ROD outlines plans for removing 18 DOE-owned structures, including the liquid sodium processing plant where the coolant for the reactors was produced, and the underground bunker where fission-powered batteries were tested that would take spacecraft like Voyager and Cassini on their journeys into space.

“DOE will prepare demolition and disposal plans for each building, which include processes for characterizing building materials; collecting, handling, transporting, and disposing of debris; and identifying permitted off-site facilities to receive the debris,” the report states. In addition, the decision recognizes that the demolition of five structures among the 18 in Area IV must be compliant with State of California permits under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act and California hazardous waste laws,” the report states.

The ROD is only the first step in this process, and Perry, the first DOE secretary to visit the site, will not be there to oversee the process. The secretary has announced plans to resign in November.

Area residents and activists continue to question the process, including how transporting truckloads of contaminated soil will impact their health and safety, and the potential effect of the mitigation work on wildlife, air quality, and one of California’s most important archeological sites, located near Area IV.

For more information on the DOE’s mitigation plan, visit SSFLAreaIVEIS.com.