For decades, it has been known that a number of Indian bones were buried all along the bluffs by the sea. Occasionally after a high tide, relics… are to be seen, the high water having removed the covering of earth and exposed them to crumble in the air. (“Skeletons and Skulls of Warriors are Excavated,” Los Angeles Times, July 19, 1910)

On June 27, 1910, a class of 30 Stanford University students and their Geology professor J. R. Pemberton pitched tents at Topanga Beach, camping (or glamping) with Japanese cooks and “everything required for [their] convenience.” The students were on a summer field trip studying oil formations, but by mid-July they were discovering Native American graves that went “far back into the range.”

In one mound, they came upon 34 skeletons, all of which appeared to have been buried at the same time. At least one of the skulls had arrowheads embedded in it, others were crushed. A Stanford Archaeology class soon arrived and conjectured that the graves were evidence of a massacre around the year 1200.

Strangely, Professor Pemberton reported that the skeletons “were almost dwarfs in size,” and confirmed seeing other abnormalities.

The brow is almost totally lacking, rising from the line of the eyebrows only three-quarters of an inch, and the top of the head being almost flat…. [The nose] projects horizontally, hornlike, and with no resemblance to the human nose. A spirit level laid from the top of the head to the tip of the nose would show but a slight inclination.

These queer tribesmen had bulging heads in the rear and unusually heavy jaw bones, due probably to their diet of clams and other shell fish, the shells of which they crushed between their teeth.

(1910-11-12, “Unheard of Race,” Marion County Progress)

Another of the skulls had horns, which protruded from near the front of the ear cavity and encircled the head. These horns, which were two or three inches in length, were apparently of the same bone composition as the skulls and had evidently been a part of them; but they were so slender and mellow with age that at the first handling after exposure to the air the horns became separated from the skull. (1911-02-05, “Will They be Interpreted?,” LA Times)

The San Francisco Chronicle called the skeletons “gigantic.”

Artifacts discovered in the mound included flint arrowheads, deer-bone whistles, shell ornaments in the shape of fish and animals, necklace beads, stone discs, mortars, and small cups with holes on either side near the top. One newspaper reported that the artifacts were unlike anything known from the surrounding Native Americans (for example, flint isn’t found in the area). Another reported that large rocks cut into the shapes of “spinning tops” resembled the fishing lures of Channel Islands Natives.

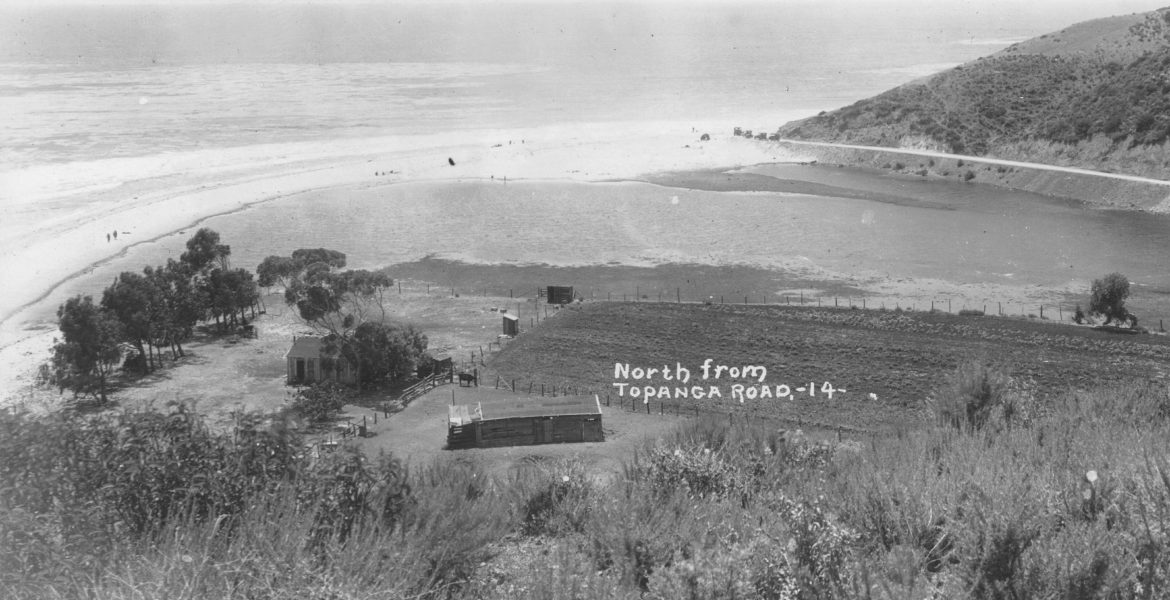

At the same time, these discoveries were being claimed by a miner and self-styled “amateur archaeologist” named W. W. Coolbaugh, who was homesteading at Topanga Beach in a roadhouse he called Jack Rabbit Lodge. He said he’d been “prospecting along the beach when he came upon a six-acre flat, at the delta of the Topango,” that had a forty-by-100-foot mound of darker soil. The mound was five to eight feet high and overgrown. Digging into it, he noticed a protective layer of boulders, then ashes and tiny seashells, and finally, whale bones covering 44 skeletons with their knees bound to their chests. Other newspapers reported that portions of more than 100 skeletons had been found, and there was speculation that 300 skeletons would be revealed when the mound was fully excavated. Men and women, young and old, were buried close together, but predominant were older men, identified by their worn-down teeth.

Coolbaugh left the skeletons “lying visible in their tombs” as a sort of attraction. By August 1910, he had begun selling artifacts to Beloit College, Wisconsin, including a four-inch arrowhead for $10. Professor Ira M. Buell of Beloit came to inspect the site. He conjectured that the burials had taken place 500 to 1,000 years ago. On the ground nearby, Professor Buell found evidence of lodge sites.

At Coolbaugh’s request, The Smithsonian Institute reportedly came to study the site, but no information could be found about their research. Coolbaugh, however, had plenty of his own conjectures to share. He imaginatively linked the graves to legends he’d heard from “the oldest Spanish families” concerning local Native Americans who’d been killed by an invasion of Aztecs from Mexico.

…in the days before the face of white men had been seen along the Coast of Southern California… there occurred an Indian massacre, when all of the inhabitants of a Topango village were killed by a marauding enemy that fell upon them. The bodies of the dead were piled in a heap, according to the prevailing custom, covered with stones, and a funeral pyre burned over their heads. The fire thus started, so the legend runs, leaped deep into the fissures between the rocks; it gave birth to the mountain, whose intermittent smoking continues to this day.

(1911-02-05, “Will They be Interpreted?,” LA Times)

The Smoking Mountain refers to a site at nearby Las Pulgas Canyon where oil deposits are suspected as the cause for an underground fire that burned for hundreds of years, and into the 20th century.

Coolbaugh was especially captivated by a polished bone statuette he called a royal scepter, comparing it to one that explorer Francis Drake observed in 1579. “The eyes and nose of the hand-made god show plainly,” a newspaper reported.

The attention Coolbaugh received must have made him more of a nuisance to authorities because, on March 22, 1911, he was driven out of his homestead by a sheriff’s deputy. As questionable as his stewardship of the Topanga Beach Native American site may have been, without him all studies ceased.

In September 1911, a silent Western film called A Chance Shot, directed by Pat Hartigan and starring Ruth Roland, was filmed in the area. Publicity for the film irreverently boasted that it had been shot at the Topanga Beach site and used its artifacts as props. It is not known if this film still exists, but the racist plot was summarized as…

Red Fox, an Indian brave, wins White Doe, the chief’s daughter, but to emphasize the fickleness of the Indian husband, he becomes enamored of Mary, a settler’s daughter. Finding that his pleas for her love have no effect on the white girl he captures her and [binds] her to a tree….(www.imdb.com/title/tt0195591)

In October 1911, dozens of graves with artifacts were discovered at Malibu beach. Similarities between the sites led to speculation that the Native Americans of Topanga Beach had made these burials too. Previously, in July 1908, 14 skeletons, purported to be seven to eight feet in stature, were found at a Malibu beach.

In September 1914, a new discovery was made at Topanga Beach by ground squirrels, whose burrows were observed to contain dark earth, human bones, and shells. The underground source of these artifacts was not found.

In 1915, new property owners began keeping people away from the site to prevent its destruction. However, Professor Buell complained that they wouldn’t allow researchers in either.

In 1916, a Tongva Native named Setimo Lopez told renowned ethnologist John P. Harrington that the word “Topanga” came from the Chumash Ventureño language, which suggested that the Chumash boundary was farther south than had previously been thought. José Maria Zalvidea, another Tongva Native, told Harrington that there had been a cemetery at Topanga Beach with whale bones as markers, and that many of his ancestors were buried there.

In January 1923, the LA Times lamented that Native American history was being lost because a new highway was being paved across the delta (instead of curving around it, as before).

In the late 1940s or 1950s, the Topanga Beach site was given the archeological site number LAN-133 by Sophie Bayler, who observed a shell midden containing beads, abalone spangles, and flint arrowheads.

In January 1950, another Native site, LAN-215, was recorded by archaeologist S. L. Peck on neighboring Parker Mesa (later Sunset Mesa). However, Peck noted that most of the site had already been destroyed by plowing.

In spring 1961, the Parker Mesa site was rediscovered by archaeologists Dr. Chester King and Tom Blackburn. Artifacts found there included bowl fragments, a basalt projectile point, a chert knife, sharpened animal bones, a partial house floor, a circular pit that may have been a yucca-roasting oven, and stones shaped into discs, mortar blanks, balls, and crescents. The Parker Mesa site was estimated to have been inhabited at least as late as 1000 B.C. Dr. King conjectured that the Topanga Beach site was populated only after the Parker Mesa site had been abandoned. Grading for the Sunset Mesa housing development began soon after the excavation, so archaeologists had little time to study this site.

In the 1960s, Topanga Beach residents found rock bowls that had been washed down the creek, and in the 1970s, residents found arrowheads, beads, grinding stones, and a carved rock that appeared to have been hung on a string.

In 1977, State Parks archaeologist P. Barclay wrote that he’d found no evidence of the Topanga Beach site and declared it completely destroyed, yet, in the 1980s, a shell midden was again reported.

In 2001, State Parks bought Lower Topanga. While taking a preliminary resources inventory prior to demolishing the houses, “eight previously unrecorded sites were discovered, containing a variety of artifacts,” according to “The Topanga Story.”

In 2002, State Parks bought a large portion of Tuna Canyon containing “several thousand Native American Indian sites,” according to “The Topanga Story.”

In 2002 and 2003, State Parks archaeological monitor Sarah Jenkins found a layer of shell fragments and artifacts buried several feet underground at Topanga Beach.

In 2004, Topanga Ranch Motel resident and Tongva tribal litigator John Tommy Rosas nominated the Lower Topanga area as a Native American Sacred Site, while fighting his and the community’s eviction.

In 2007, the year the last houses were bulldozed, further State Park monitoring revealed shell midden and “prehistoric artifacts” on the ground at LAN-133 and nearby. Because the earth had been moved around, the discovery couldn’t be attributed to LAN-133 with certainty, so it was given the separate site record LAN-3759.

‘The Topanga Story’ conjectures that Topanga Beach was the site of the original Native American Topanga village, from which the rest of the canyon derived its name, just like at Malibu, where the contemporary name comes from the name of the Chumash village.

Only six people from the village Topanga are recorded in Mission records. They are Luis Juan Athacge of Topabit, 17 (baptized on August 19, 1793), Juan Antonio, 50 (baptized in 1800), and four children (baptized on March 6, 1803).

Pablo Capra is a former Lower Topanga resident, and continues to preserve the history of that neighborhood on his website, www.brasstackspress.com, and as a board member of the Topanga Historical Society, www.topangahistoricalsociety.org

Are there photos to go with the discoveries?

Yes, there are some photos in the original LA TIMES articles about this discovery. The Santa Monica Public Library also has a photo in its archives that I was told is likely from this site.

Fascinating. Thank you!

Are any of the artifacts in a museum? Please let us know, thanks.

thank you

Thank you Pablo. Particularly important as we navigate the cleanup after the Palisades Fire